Story 1: The connection between Sugar - Students - Teachers

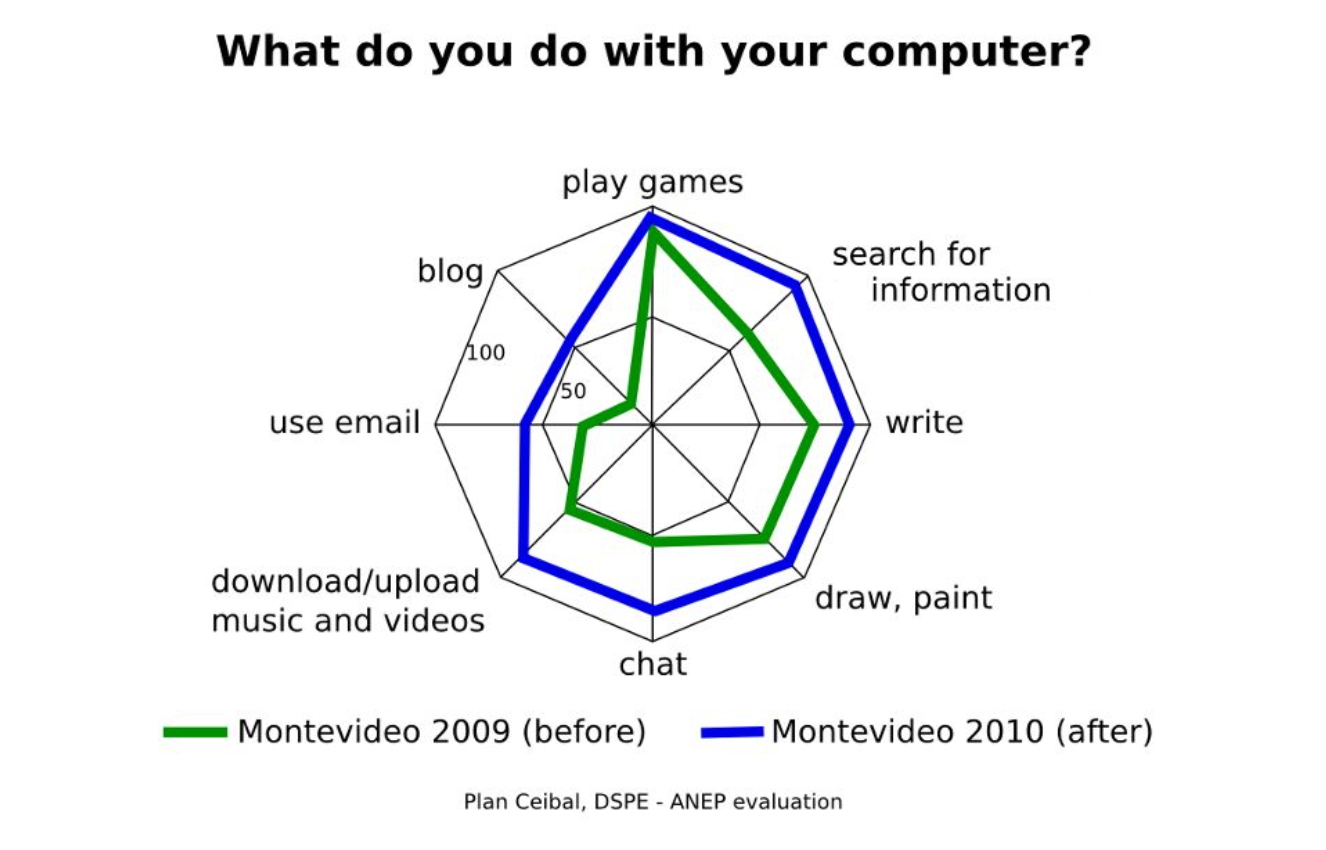

One of the first formal studies of Sugar took place in Uruguay in 2009–10. Uruguay was the first country to provide every child a free internet-connected laptop computer. They began distributing OLPC XO laptops running Sugar in 2007. Even though Uruguay is a relatively small country, with less than 500,000 children, it took several years before they could achieve full coverage. The last region to receive laptops was Montevideo. Montevideo was last because there was less need there than in the more rural regions, since many urban children already had access to computers. The delay in deploying in Montevideo presented an opportunity to study the impact of Sugar. Children were asked in 2009—before they has Sugar—what they did with their computers. It should come as no surprise that they used their computers to play games (See Figure). The same children were asked in 2010—after almost one year of using Sugar—what they did with their computers. Again they responded that they used their computers to play games. They were still children after all. But they also used their computers to write, chat, paint, make and watch videos, search for information, etc. In other words, with Sugar, they used the computer as a tool. Children play games. But given the opportunity and the correct affordances, they can leverage computation to do much much more.

Figure: Data from a DSPE-ANEP survey of students in Montevideo before and after the deployment of Sugar

Sugar was designed so that new uses emerging from the community could easily be incorporated, thus Sugar could be augmented and amplified by its community and the end users. We encouraged our end users to make contributions to the software itself. This was in part out of necessity: we were a small team with limited resources and we had no direct access to local curricula, needs, or problems. But our ulterior motive was to engage our users in development as a vehicle for their own learning.

One of the first examples of end-user contributions took place in Abuja, Nigeria, site of the first OLPC pilot project. While teachers and students took to Sugar quickly, they did confront some problems. The most notable of these was that the word-processor application, Write, did not have a spelling dictionary in Igbo, the dialect used in this particular classroom (and one of the more than three-hundred languages currently spoken in Nigeria). From a conventional software-development standpoint, solving this problem (300 times) would be prohibitively expensive. But for children in Abuja, equipped with Sugar, the solution was simple: confronted with the problem of lacking a dictionary, they made their own Igbo dictionary. The did not look for others to do the work for them. The took on the responsibility themselves. The Free/Libre Software ethic built into Sugar enabled local control and innovation.

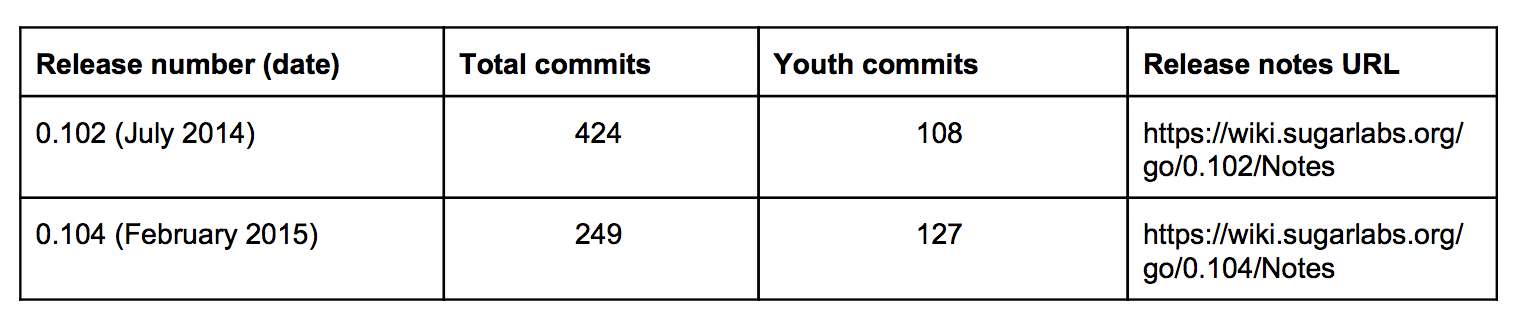

John Gilmore heard the about our aspiration to reach out to our end users—children—at the 2008 Libreplanet conference. He asked, “how many patches have you received from kids?” At the time, the answer to his question was zero. But over the past nine years, the situation has changed dramatically. By 2015, 50% of the patches in our new releases were coming from children (See Table); our release manager in 2015–16 (Sugar v0.108) was Sam Parkinson, a fifteen-year-old from Australia; our current release manager (Sugar v0.110) is Ignacio Rodríguez, an eighteen-year-old from Uruguay who began hanging out on our IRC channel at age ten and contributing code at age twelve.

Table 1: Sugar commits by youth contributors

When the now former president of Uruguay, José Mujica, learned that a twelve-year-old from a small town east of Montevideo had programmed six entirely new Sugar activities for the XO, he smiled and said triumphantly: “Now we have hackers.” In his eyes, this one child’s ability to contribute to the global Sugar development community was a leading indicator of change and development in his country.

None of this happened on its own. End-user contributions are not simply an artifact of Sugar been Free/Libre Software. Open-source Software gives you access to the code and that Free/Libre Software gives you a license to make changes. But without some level of support, very few people will have the means to exercise the rights granted to them under the license. For this reason, we built scaffolding into Sugar to directly support making changes and extensions to Sugar applications and Sugar itself.

Sugar has no black boxes: the learner sees what the software does and how it does it. Sugar is written in Python and comes with all of the tools necessary to modify Sugar applications and Sugar itself. We chose Python as our development language because of its transparency and clarity. It is a very approachable language for inexperienced programmers. With just one keystroke or mouse click, the Sugar “view source” feature allows the user to look at any program they are running. A second mouse click results in a copy of the application being saved to the Sugar Applications directory, where it is immediately available for modification. (We use a “copy on write” scheme in order to reduce the risk of breaking critical tools. If there is no penalty for breaking code, there is better risk-reward ratio for exploring and modifying code.) The premise is that taking something apart and reassembling it in different ways is a key to understanding it.

Not every creative use of Sugar involves programming. Rosamel Norma Ramírez Méndez is a teacher from a school in Durazno, a farming region about two-hours drive north from Montevideo, Uruguay. Ramírez had her lessons for the week prepared when, first thing Monday morning, one of her students walked into her classroom holding a loofa. The child asked Ramírez, “teacher, what is this?” Rather than answering the question, Ramírez seized the opportunity to engage her class in an authentic learning experience. She discarded her lesson plans for the week. Instead, on Monday the children figured out what they had found; on Tuesday they determined that they could grow it in their community; on Wednesday they investigated whether or not they should grow it in their community; on Thursday they prepared a presentation to give to their farmer parents on Friday about why they should grow this potential cash crop. Not every teacher has the insight into learning demonstrated by Ramírez. And not every teacher has the courage to discard their lesson plans in order to capture a learning opportunity, But given an extraordinary teacher, she was able to mentor her students as they used Sugar as a tool for problem-solving. Ramírez encouraged her students to become active in their learning, which means that they engaged in doing, making, problem-solving, and reflection.

“Teachers can learn (and contribute) too.” – Walter Bender

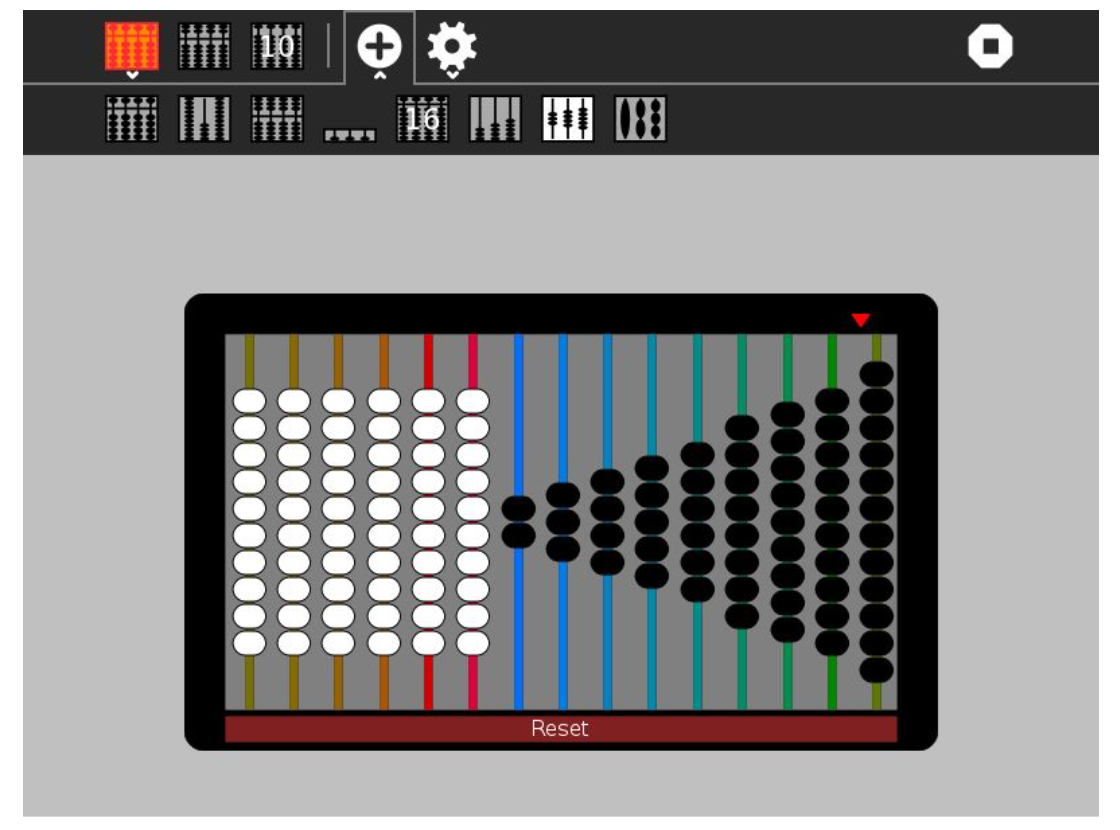

Sometimes teachers have been directly involved in Sugar software development. Sugar has an abacus application to help children explore whole-number arithmetic and the concept base (the activity allows the user to switch between various base representations of whole numbers). It also lets children design their own abacus. Teachers in Caacupé, Paraguay, were searching for a way to help their students with the concept of fractions. After playing with the Sugar abacus activity, they conceived and created—with the help of the Sugar developer community—a new abacus that lets children add and subtract fractions (See Figure). Sugar didn't just enable the teachers to invent, it encouraged them to invent.

Figure: The Caacupé Abacus. The white beads represent whole numbers. The black beads represent fractions.

Guzmán Trinidad, a high-school physics teacher from Montevideo, Uruguay and Tony Forster, a retired mechanical engineer from Melbourne, Australia collaborated on a collection of physics experiments that could be conducted with a pair of alligator clips and a small collection of Sugar applications. In the process of developing their experiments, they maintained regular communication with the developers, submitting bug reports, documentation, feature requests, and the occasional patch. Other examples of teacher and community-based contributions include Proyecto Butiá, a robotics and sensor platform build on top of Sugar (and GNOME) at Facultad de Ingeniería, Universidad de la República, Uruguay. Butiá inspired numerous other robotics platforms, e.g., RoDI (Robot Didáctico Inalámbrico) developed in Paraguay, as well as a wealth of projects aligned with the pedagogy of Constructionism. In the spirit of Sugar, these hardware projects were all designed to be “open”: schematics and firmware were made available under Free/Libre licenses.

In 2012, we were part of a team running a week-long Sugar workshop for more than 60 teachers who had traveled to Chachapoyas, the regional capital of the Amazonas region of Peru. During the day we spend time reviewing the various Sugar activities and discussing strategies for using Sugar in the classroom. In the evenings, we gave a series of optional workshops on specialized topics. One evening, mid-week, the topic was fixing bugs in Sugar. It was not expected that many teachers would attend—in part because we were competing with an annual festival and in part because their background in programming was minimal. But almost everyone showed up. In the workshop, we walked through the process of fixing a bug in the Sugar Mind Map activity and used git to push a patch upstream. Teachers, especially rural teachers, have a hunger for knowledge about the tools that they use. This is in part due to intellectual curiosity and in part due to necessity: no one is going to make a service call to Amazonas. As purveyors of educational technology we have both a pedagogical and moral obligation to provide the means by which our users can maintain (and modify) our products. Enabling those closest to the learners is in the interest of everyone invested in educational technology as it both ensures viability of the product and it is a valuable source of new ideas and initiatives.

References

- Ceibal Jam (2009). Convenio marco entre la Asociación Civil Ceibal Jam y la Universidad de la República.

- DSPE-ANEP (2011). Informe de evaluación del Plan Ceibal 2010 . Administración Nacional de Educación Pública Dirección Sectorial de Planificación Educativa Área de Evaluación del Plan Ceibal.